She was mentally ill, and this mental illness both illumined her work and colored her perspective. She had complicated and human relationships. She was a woman living in a time of great social restriction for women.

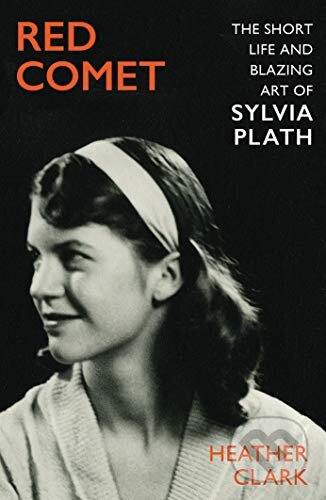

We get the full scope of Plath’s incredible talent here, rightfully established as complicated, radiant and worthy of deep consideration. Her husband, Ted Hughes his lover, Assia Wevill Plath’s mother, Aurelia Plath-they are not villains but people who created art of their own, who loved and fought with Plath, who were not always good or right.Ĭlark’s detailed, multidimensional treatment gives Plath’s life and work its dignity, character and sense of interiority. She also liberates the supporting cast of Plath’s life from the damning and one-dimensional roles they often occupy as part of the death-myth of Plath’s life. In the massive effort that is Red Comet, Clark admirably identifies and resists the morbid tendency to look at every moment, every work, as a signpost on the way to Plath’s tragic suicide. (There is, of course, the larger question of why we label art consumed by teenage girls as unintelligent and lesser.)īiographer and Plath scholar Heather Clark lifts the poet’s life from the Persephone myth it has become and examines it in all its complexity. Her name comes up again and again alongside figures such as Lana del Rey in articles referencing the “sad girl aesthetic.” When my daughter saw my copy of Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath lying bricklike by my chair, she reacted with surprise: “Oh! They sing about her in the Heathers musical!” Somehow this poet, named a genius in her lifetime, is now deemed “confessional” and relegated to a literary space where intellectuals raise their eyebrows knowingly and dismiss her work to 16-year-old-girl-land.

These days, Sylvia Plath is often considered part of the intense realm of the teenage girl.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)